After more than two years without leaving China, Chinese president Xi Jinping chose the SCO summit in Uzbekistan last week for his return to the international diplomatic stage. Contrary to Western media claim that this was a sign of weakness or isolation, the choice of destination shows Xi’s confidence in the prospect of a region that in Western eyes has been a remote backwater. Given the relevance of the leaders of China, Russia, India, Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey among others all meeting in one place, it is surprising how little Western media reported about it. A lot of this has to do with classic Western arrogance that blinds them from seeing the real significance of countries outside of the political West. “If the US isn’t involved, it can’t be relevant” is deeply engraved in the minds not just of Americans, but also of many Europeans, especially politicians and journalists.

Another reason why many in the West have difficulty grasping what has happened at the SCO summit is their sheer ignorance about Central Asia, which is one of the few regions never colonized by a Western power. Therefore, Western European countries don’t have a deep connection with and history of exploitation in the region; unlike with India, most of Southeast Asia, some coastal cities of China, most of Africa, and the Americas. They may have heard of countries like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, or Turkmenistan in the West, but who could confidently claim to know anything about them?

Understanding the history and complexity of this region is prerequisite for grasping its centrality for present and past events. Only then can one realize the incredible success the SCO has had in developing a new order for the region, a new form of inter-state cooperation and peaceful development, and how dramatically the positive shaping power of China beyond its borders has grown over the last 20 years.Therefore, this article gives a brief geographic and historic overview, though by no means comprehensive, before looking at the geopolitical implications of the SCO, and China’s role in it.

Historically, the endless steppes of Central Asia have been very scarcely populated by nomadic peoples, and over millennia been the origin of overwhelming nomad invasions into the sedentary civilizations. Such invasions are recorded throughout Chinese history on the east of the steppes, as well as in European history to the West, such as the Huns’ and the Mongols’ incursions. But even before the ancient Greeks, in the early iron age the Persians recorded nomadic hordes from the north invading their lands in present-day Turkey and Iran. Especially the Chinese have a very long recorded history of using trade, marriage, defense walls, and military force to deal with this constant threat from their west.

In modern times, much of the Central Asian steppes were conquered and colonized by the Russian empire before being integrated into the Soviet Union at the end of World War I. During the Cold War, the US considered the region the “soft underbelly” of the USSR, always looking for ways to connect to nationalistic or religious groups willing to stand up against the other superpower.Of course, one of the southern-most of these “stans” (countries whose names end in -stan) is of course Afghanistan, where the US invested heavily in Islamist religious resistance against the socialist government supported by the USSR, drawing Soviet forces into a costly war that contributed to the demise of the superpower. The US partnership didn’t last, however, and soon enough the US saw itself drawn in an equally devastating war in Afghanistan, which cost the US more than $2 trillion, thousands of lives, and ended in an embarrassing defeat in 2021.

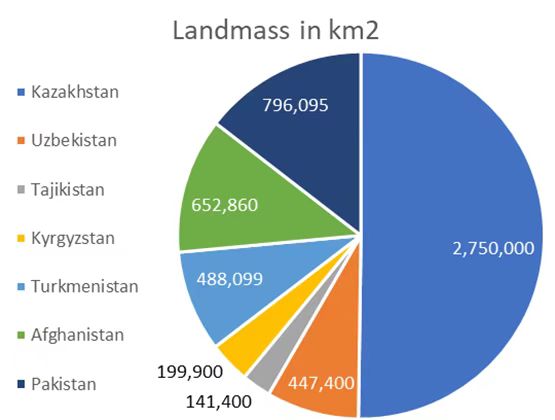

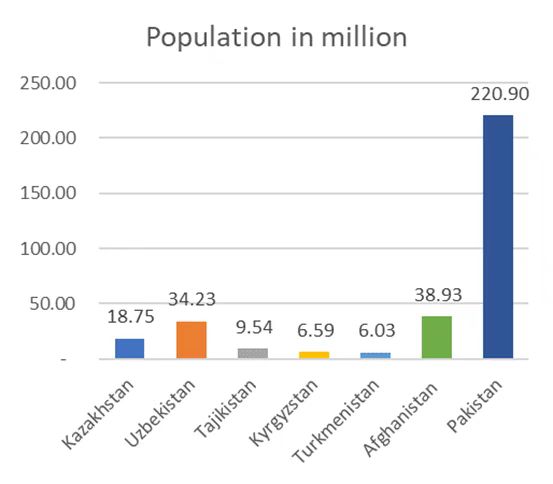

Geographically, the first obvious fact about the Central Asian region is that it’s vast, endless. The biggest of the “stans” is Kazakhstan, the world’s 9th largest country by area. Compared to Europe, take the whole area of Spain, France, and Germany combined, and then double it, or compared to the US, it is slightly bigger than the entire Midwest.Neighboring Uzbekistan is somewhere between Germany and France in size, slightly larger than California, and even the “dwarfs” like Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan each is twice the area of the entire Benelux region, or half the size of Germany, bigger than New York State. Similarly diverse are the population sizes and the levels of economic development of each country. The most populous “stans” (except Pakistan with 220 million people and a landmass the size of Turkey) are Afghanistan and Uzbekistan each with around 35 million people, the vast Kazakhstan only has about 19 million inhabitants, and the smaller Turkmenistan (which as a neutral country and not a member of the SCO), Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have just 6 to 9 million inhabitants each.

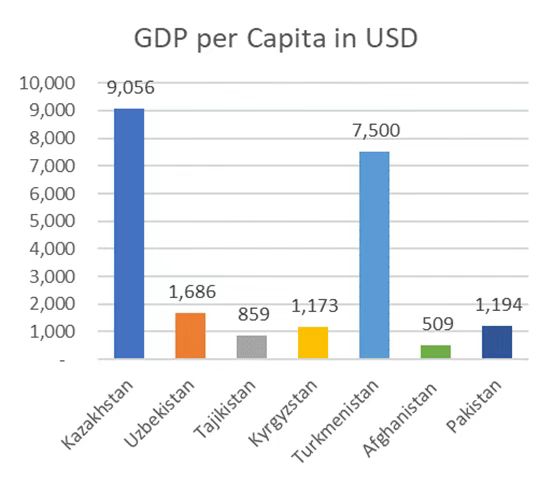

The poorest country in terms of per capita GDP is Afghanistan, after 40 years of war and turbulence, with a shockingly low $509 a year. But Tajikistan isn’t much better off with just $859 a year. By contrast, the very secluded Turkmenistan comes up to $7500, roughly 4 times higher than India, and oil-rich Kazakhstan is solid in the upper middle-income bracket with $9,056 per year. And such differences don’t even touch upon the diverse languages, cultures, traditions, and historic views of the region. Although mostly Muslim majority, the importance and variations of religion in people’s lives also differ dramatically from country to country.

Given the central location of this “Eurasian heartland”, it will become increasingly important for the geopolitically interested. The geostrategic importance becomes obvious when one looks at the countries bordering this region: Russia in the north, China in the east, and India to the southeast of Afghanistan and Pakistan, the southwest is bordering Iran, and in the west lay Azerbaijan and Armenia leading onward to NATO member Turkey. This is the tremendous scope of the SCO, covering not just the recent hot border conflicts between Azerbaijan and Armenia, and between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, but also the long-standing Pakistan-India dispute, the India-China border dispute, and negotiations are well underway to allow Middle Eastern countries to join the SCO, with all their internal tensions and contradictions. This reminds us of the time when the British Empire fell apart, in the power vacuum a variety of very diverse nations came together to form the League of Nations and later the UN, where countries would talk, despite all differences. Indeed, the original spirit of the UN, where even at the height of the Cold War the US would keep up negotiating with the USSR, seems to be alive and well in the SCO, whereas the West increasingly chooses a path of exclusion, isolation, sanctions, the US prevents half the Russian delegation from attending the UN General Assembly, and disinvited countries it doesn’t like from the Summit of the Americas.

The comparison to the founding of the UN is of course limited, and while the decline of the US empire may be compared to some extend with the dissolution of the British Empire, the SCO is not there to replace a previous order, but rather to revive it. The UN won’t be replaced by the SCO. Nonetheless, the SCO is bigger than just a regional organization like the EU, and by contrast it is more open, flexible, and less restraining for member countries. It is a distinctly Asian organization in that it doesn’t try to create restricting norms and overreaching international courts to restrain individual countries, like many Western-led supranational organizations. Instead, it’s a forum for negotiation, to seek beneficial cooperation where it is possible, without pretending all problems could be solved this way. While the EU currently faces a number of countries having left or thinking about leaving, the SCO is expanding and many countries are eager to join.

The SCO was founded in 2001 with only 6 members and has increased slowly in number of participants and projects. Xi Jinping’s role in driving the SCO forward can hardly be overstated: shortly after the Chinese Communist Party elected him chairman in 2012, he proposed the very successful Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank and the “Belt and Road” initiative in 2013, both aiming at turning Central Asia from a remote, impoverished backwater into a central, prosperous core for a pan-Eurasian trading network, greatly increasing the importance of the SCO as a political forum to discuss security, peace, cultural exchange, and economic cooperation, as a basis for growing prosperity across Central Asia. Just two years later, in 2015, the SCO grew dramatically in scope and importance by admitting both India and Pakistan – two nuclear powers with a total population almost equivalent to China and Russia’s – into the organization. In this light it should be no surprise that Xi attached such great importance to the SCO summit and chose it as the destination of his first trip outside China in more than two years. According to Chinese government spokespeople, he attended nearly 30 official events in two days, so the trip was also an example of highly efficient Chinese diplomacy.

(Contributed by Harald Buchmann, Intellisia Senior Research Fellow, for Guangming Online)

点击右上角![]() 微信好友

微信好友

朋友圈

朋友圈

请使用浏览器分享功能进行分享