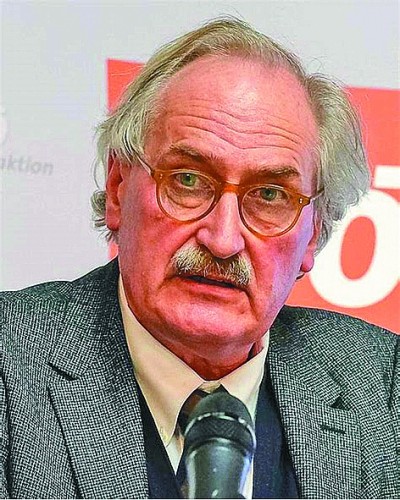

Axel Honneth is one of Germany's leading social theorists and philosophers. He was director of the Institute for Social Research at the University of Frankfurt. He is the third-generation figurehead of the Frankfurt School and the leading exponent of modern Western recognition theory. His masterpiece is Struggle for Recognition – The Moral Grammar of Social Conflict. He currently teaches in Germany and the United States.

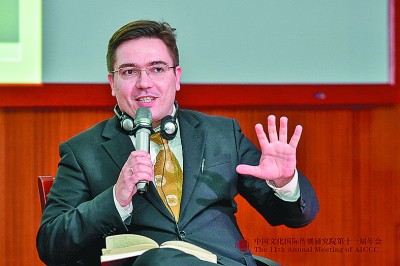

David Bartosch is a member of the German Society for Intercultural Philosophy and works as a contract professor at the School of International Relations at Beijing Foreign Studies University. His most important opus to date is ‘Knowing Unknowing’ or 'Good Knowing'? On the Philosophical Thought of Nicolaus Cusanus and Wang Yangming.

Xue Xiaoyuan is a professor at the Center for Globalization and Cultural Development Strategies at Beijing Normal University. A representative work of his is the study written in Chinese: The Beauty of Flying Motion: The Understanding and Interpretation of "Dynamic Beauty" in Chinese Culture.

1. No country is immune to the pandemic

Xue Xiaoyuan: Dear Mr Honneth and Mr Bartosch, it is my great pleasure to be here discussing with you on the platform of the Guangming International Forum. The novel COVID-19 pandemic has so far infected nearly 100 million people and claimed nearly 2 million lives, with more than 20 million cases in the United States alone. How do we view and assess this huge and far-reaching global pandemic?

Axel Honneth: It is almost too early to answer this question in a satisfactory way today. Certainly, one of the first consequences of the pandemic is that, like hardly any other event before, this has made us feel the global connectedness of all people as well as the many differences between them at the same time. On the one hand, it quickly became apparent that, due to worldwide mobility, no country could protect itself from the virus and thus we have all long since formed a global community; on the other hand, it quickly also became obvious to everyone that the various countries would react to the crisis by applying very different measures. This is due to the differences in the political constitutions and, correspondingly, in the health systems. Perhaps one could say that we go through a first-time experience of difference in global unity. Furthermore, it was of course astonishing how quickly there was a worldwide reassessment in the ranking of system-relevant activities and tasks to be observed; suddenly the curative, caring work, which otherwise tended to be in the shadow of other supposedly exclusive, namely value-creating activities, seemed to be of greater value to all of us than the industrial or service-providing work. In Germany, for the first time, unfortunately much too late, the question of what actually makes a job "system-relevant" was publicly discussed; and at least for a brief moment, the thousands of nurses and geriatric care workers, who until now had done their daily work with poor pay and little recognition, deprived of any major attention, suddenly met the public eye. We will have to see if this re-evaluation of the old hierarchy of work and profession will survive the pandemic and have a longer-lasting effect. Finally, in the wake of the crisis, at least in this country, something like a collective rethinking of the value of friendships and family relationships has taken place.

David Bartosch: Viewed through the lens of Mr Honneth's theory of recognition, the global devastation of the new COVID-19 pandemic has made it clear that we do indeed exist in an inseparable global community, but that the inevitable differences of historical backgrounds, mentalities, political and economic situations of nations has led to multi-diversity within global integration. Based on this basic dialectical understanding of globalisation, Mr Honneth further argues that curative professions have so far been much less appreciated and recognised in society than industrial or other, namely service-providing industries. This criticism also implies a critique of capitalism. In his social philosophy, Mr Honneth assumes that the attainment of happiness by all members of society is the highest good, whereby the just distribution of social resources and economic benefits is only one prerequisite; above all, mutual legal, moral and social recognition by all participants is also important.

Xue Xiaoyuan: Mr Honneth, you are considered the leading representative of recognition theory. Most of your writings have been translated into Chinese, they have become an important reference for the Chinese world in terms of actuality and reality-oriented thinking. Can we proceed from the base point of the theory of recognition to explore what we should recognise as a priority in the midst of the new kind of pandemic now as it rages around the world?

Axel Honneth: In optimistic moments, I hope, as I said, that the pandemic could lead to a reassessment of the recognition of social work, leading away from a one-sided esteem for mere manufacturing, so-called "productive" activities and towards a stronger recognition of all curative activities that take care of our physical well-being. In addition to this optimistic expectation, I would also like to see a change in the relationship of recognition between states; if things go well, the pandemic crisis could also lead to the individual states learning to see themselves as members of a global community of destiny (German: “globale Schicksalsgemeinschaft”) and thus focus more on cooperation than on competition in the future. But, as mentioned before, only in moments of hopeful confidence do I really believe that such transformations in social and international relations of recognition might actually take place as a result of the pandemic.

David Bartosch: The ideal of a perfect and completely self-integrated humanity and lasting world peace continues to drive us in the hope of realising a better future. In the 21st century, we must completely re-orient ourselves: the goal is to achieve universal human recognition. Mr Honneth calls for more cooperation between nations instead of competition. His attempt also brings love, friendship and mutual solidarity to the fore as the highest moral standards and as core values of a future international community. It is perfectly obvious that only in this way we will be able to achieve lasting happiness and the ability to survive in the long term as a global community. It is also consistent with the principle of a "community of shared future for mankind" proposed by President Xi Jinping.

2. The protection of individual life takes precedence over the satisfaction of individual arbitrary freedom

Xue Xiaoyuan: What is more important for individuals, societies, peoples, nations, or even for the world and humanity as a whole – freedom or life? At this critical moment in our lives, this is an important topic for us to reflect on deeply and then also to make a decision. What do you think about this?

Axel Honneth: Regarding this question, which is indeed very central today, I have a clear and quite unshakeable conviction. It will perhaps surprise all of those who primarily see me as a freedom theorist: Regardless of how our liberties are legally defined in a state, we can only exercise and enjoy them on the condition that we are physically unharmed and therefore as far as is individually possible enjoy physical health. In this respect, in my opinion, the imperative to protect individual life precedes the granting of individual arbitrary freedom. However, this precedence does not, of course, imply a carte blanche for states to arbitrarily restrict fundamental freedoms in favour of the protection of bodily integrity; any restriction of this kind requires public justification because, in principle, it must be made clear to all citizens in a comprehensible and convincing manner which measures just taken serve which purposes of protecting life and why they require the restriction of certain of the legally guaranteed freedoms. Thus, the primacy of the protection of life is tied to the condition of public and generally comprehensible justification of each individual measure that restricts our legally guaranteed freedoms.

Xue Xiaoyuan: In Suffering from Indeterminacy. An Attempt at a Reactualisation of Hegel's Philosophy of Right (2001) you say that in friendship and love, for example, there is true freedom. Here one is not unilaterally limited to oneself, but one enjoys limiting oneself in relation to another, and one knows oneself in this limitation as the performing self of this limitation. I think there are two implications of your thinking: the relationship of self and other and the relationship of freedom and limitation. Could you please elaborate on that?

Axel Honneth: Yes, you are absolutely right, these are probably two different theoretical steps. First of all, one has to realise that freedom always means subject yourself to certain norms, because otherwise we would only be controlled by causally effective impulses or forces. This is the great insight of Rousseau which Kant then was able to process further, namely in order to come to the conclusion that we can only be truly free if we ourselves limit our actions by submitting to the inherent principles of practical reason. To this first step, Hegel then added the further idea that this moral law means nothing else than obtaining the consent of all other persons concerned for one's own intentions to act – and thus the idea was born that we are only free when we are in a relationship of mutual recognition with others, which means to jointly subject ourselves to the reciprocally accepted norms. In this respect, freedom means limiting oneself in one's intentions in relation to other persons by mutually subjecting ourselves to norms that are jointly considered to be correct, whereby we simultaneously recognise each other reciprocally as equal and free beings.

David Bartosch: By making use of the philosophical keyword "liang zhi" and other terms, the Chinese Ming dynasty philosopher Wang Yangming already discussed the idea of (good) conscience rather early on: In this context, it is precisely the question of shared responsibility and recognition between man and man and between man and society that is at issue. In relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, unluckily some people confuse freedom with ego-centeredness, and in some countries some people equate refusing mandatory mask-wearing with "freedom". This is, of course, utterly wrong. Those who do not wear a mask in these cases are not making their own personal choices but are potentially putting others at risk. True freedom does not mean to arbitrarily do whatever one feels like doing irrespective of the consequences for others; one only acts freely as far as one recognises others as equally entitled subjects in terms of legal and moral responsibility. If someone refuses to wear a mask in this case, they are potentially depriving others of their health and thus of the opportunity to exercise their respective personal freedom – and therefore they are also forfeiting their own. When societies or state structures collapse due to a pandemic, there will be nothing left to guarantee the freedoms hat we are used to. Therefore, by wearing a mask to protect ourselves and – more importantly: others from potential infection by the virus, we are actually protecting our own freedom and the freedom of others, as well as the society which we live in, and even other societies in other countries. Of course, Mr Honneth is right when he says that pandemic-related restrictions regarding the limitations of personal freedoms must be appropriately reflected and justified in public. The serious problems posed by the new COVID-19 virus should lead all of us worldwide to learn and discuss again what it means to take personal responsibility for the good of all of us on this planet. If more and more people all around the world would learn to act as conscientious subjects in this regard, it will be much easier to solve other global challenges as well.

3. Social freedom that incorporates solidarity and cooperation represents the highest form of individual freedom

Xue Xiaoyuan: We also note that you distinguish three forms of freedom: negative freedom, freedom of choice and freedom of association, which you call legal freedom, moral freedom and social freedom in your book Freedom’s Right. Can you please explain why you have compartmentalised these concepts of freedom in this way? What are their connotations and boundaries? Why is it necessary to formally rename them? What explanatory power and relevance does your theoretical model have for people who are severely affected by the pandemic?

Axel Honneth: Let me answer the question as briefly as possible: In translating what is conventionally called "negative freedom" into the concept of "legal freedom", I follow Hegel, who thinks that what is specific to this form of freedom is that we are allowed to do everything that does not violate the legally defined freedoms of all others – which means that we are allowed to do everything at will that is legally permitted, so that no social connection is established and we remain "private" subjects, thereby solely dependent on ourselves. With "moral freedom", the degree of consideration for others already grows, because this requires us to check our actions to see whether they are compatible with the principle, gained in solitary reflection, of serving the good of all and thereby promoting the common good. Although this already includes the interests and concerns of all other fellow subjects in the realisation of individual freedom, these others remain completely abstract quantities that do not yet possess any social reality and therefore do not have any concrete claims on me. "Social freedom", i.e. the highest form of individual freedom, is now much more than what you have referred to by the expression "freedom of association"; it is not the freedom to be able to enter into associations with others as a matter of principle, but rather the freedom to align one’s goals, if possible, with the goals of concrete others in such a way that we can realise them only together by means of respective interaction – of which friendship provides the best example perhaps, and although every active cooperation represents the case of such kind of social freedom. This form of freedom cannot even be adequately formulated in legal terms, since it depends on the concession of institutional conditions in which we can only realise our goals if other persons possess complementary goals – as in friendship, as in every political movement or in the democratic formation of public will.

David Bartosch: In this context, Axel Honneth starts from theoretical elements formulated in Hegel's Elements of the Philosophy of Right. For Hegel there are two basic forms of individual freedom: voluntary recognition of the legal status of another as a legal person equal to me and voluntary recognition of another as a subject of moral action equal to me. If I wear a mask during the pandemic because the law requires it, I thereby recognise the other person's right to his/her own healthy body, which I am not allowed to harm. I exercise moral freedom when I put on a mask in a situation of justified risk of infection even if I am not compelled by a legal regulation to do so. In Honneth's terms, social freedom is represented in actions in which everyone uses their free will in the interest of everyone else in particular and therefore in the interest of all others. This involves solidarity in matters of health, towards the vulnerable, the elderly, but also more generally in a reciprocal sense: as an expression of a responsibility of all individuals towards all others. We learn this in the recognition of others in friendship and love, by training our conscience and through the experience of love and care within the family. The resulting solidarity between people is a fundamental factor in stabilizing society and making it sustainable as a whole. Hegel one-sidedly misunderstood civil society as a purely competitive process. Mr Honneth's reflections on social freedom, on the other hand, therefore represent an important advancement. He extends the category of social quality, which Hegel wished to be confined to friends and family members, to the entire social realm. Again, intersections of Honneth's thinking with Wang Yangming's ideas can be found. Moreover, social freedom should be realised not only at all levels of a country's society but also in the cooperation of governments and their representatives, because only in this way the paramount idea of a shared happy future for humanity may become reality.

4. Not to "reify" and not to forget all the suffering caused by the pandemic

Xue Xiaoyuan: In Reification – A Recognition-Theoretical Study, we read about your deeper implications regarding the theory of recognition: recognition in the sense acknowledging is prior to cognition, recognition of nature, recognition of the unknown self and recognition of oblivion. Can we use this understanding to recognise, analyse and study the origin, spread and deterioration of the pandemic situation? How can a rational and objective basic attitude prevail with regard to people's perception in the face of such a pandemic?

Axel Honneth: The concept of "reification", which I adopt in order to modify it slightly, refers to a phenomenon that certainly does not occur all too often, but which is nevertheless very drastic in social terms: it is a type of human behaviour that is no longer able to perceive what is actually human in other people as well as in oneself, i.e. the subjective core of the ability to suffer and of vulnerability, so that in the end the others, as well as one's own self, are treated only as a "thing", as a soul-dead object that can be manipulated at will. In my perception, such reifying behaviours are typically triggered by people being forced to engage in procedures which, due to their constant repetition, tend to make them forget the subjective core of all sentient beings in others and/or in themselves. This is why I am referring to "reification" as a forced "oblivion" of recognition, since our "normal" attitude towards others as well as towards ourselves is that of recognising this common ground in vulnerability and sentience. A typical example is the practice of military practices sustained over a long period of time, the result of which is that those affected become accustomed, as it were, to a totally reified way of dealing with themselves and other people. This could very aptly explain certain borderline situations of the complete derailment of the very basic human relations – take incidents such as the quasi-industrial killing of completely innocent children in the Nazi concentration camps.

David Bartosch: One may add that the "oblivion" of recognition does not always have to be a direct result of dull, repetitive actions, but can also come quietly because people do not perceive or feel the suffering of others directly. In today's society, whether in countries severely affected by the pandemic or in war-torn places, people should never be "reified" and treated as cold numbers in statistics. The suffering of millions of individuals and families should not be allowed to disappear and to be vanished in oblivion behind quantitative categories like that. It is also shocking that countries that preached herd immunity in the beginning have so openly "reified" their elderly, sick and disabled citizens. Therefore, after the successful containment of the pandemic, we should be careful not to "reify" and forget all the suffering caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Xue Xiaoyuan: In the post-pandemic period, how should we build relationships of trust, self-esteem and pride between people, between individual and society, between people and country, and between countries?

Axel Honneth: I have already implicitly provided an answer to this in the context of the first questions. I think that in the most fortunate case, the current crisis can make us aware of our profound dependence on a complete multitude of relations of recognition that we tend to lose sight of in the spirit of constant bustle and economic productivity. It all starts with the fact that facing physical suffering, the threat of illness and rampant death makes us realise that the intimate relationships of friendship and family are the sanctuaries where we can articulate our fears and hope for loving support and comfort, protected from exposure and ridicule; only here, in the private sanctuary of friendship and family, can we get rid of the tormenting feeling of being completely on our own in the face of the existential vulnerability of our existence and of having to face our demise in loneliness. If we are members of a civil society in which we respect each other as equals and fight together for more just conditions, this can provide us with the courage and hope to be able to change something for the better in the current crisis by virtue of our power of solidarity – for example, to force our governments to work harder to establish largely free, technically well-equipped health systems. At best, the pandemic will also make us aware that we are dependent on the cooperation of all individual states in overcoming the great challenges of our time and that each of us has therefore potentially long since been united with everyone else on this planet through invisible relations of recognition – the great "family of humanity", as it was once emphatically called, to which we all have always belonged, as we realise today, because we are threatened by the same global catastrophes regardless of status and rank. But as mentioned before, if you ask me whether there will now be a rapid change in consciousness due to the crisis and whether we will suddenly learn to recognise our reliance on all these relations of recognition, my optimism is very limited.

5. Recognition of the value and dignity of life is a precondition for building a human community of shared destiny

Xue Xiaoyuan: Prof Honneth, you suggest that the social recognition of the quality of the relationship should form the basis for a conception of social justice. You have also argued that Hegel's theory of justice is linked to the idea of treating a disease, the diagnosis and treatment of which has a socio-critical function. How can social justice be achieved based on a theory of recognition in today's international community during a time of malady?

Axel Honneth: The view still prevails that justice merely consists in a fair, egalitarian distribution of certain "basic goods". This idea is misleading because "injustice" usually does not result from an unequal distribution of resources but from a violation of freedom and a disregard of claims to be treated fairly and respectfully. If we understand justice in this "relational" sense and thus focus on the relationships between subjects, it quickly becomes clear that it is primarily about the establishment of social relationships in which everyone, whether woman, man, believer or non-believer, black or white, can autonomously shape his or her life by being equally respected in the different social spheres and accordingly being able to participate on an equal footing in the shaping of these spheres without restriction or coercion. The measures necessary to free individuals from coercion, dependence and disregard and to enable them to participate equally in the shaping of their spheres of life change depending on the social situation, historical situation and cultural conditions. So, what justice requires in each historical moment cannot be determined from the high vantage point of philosophy, but rather philosophy must make itself the representative and advocate of those countless people who suffer in concrete terms from unequal treatment and disregard in each case – to help these people articulate their needs through conceptual means and then, by virtue of theoretical imagination, to draw conclusions regarding appropriate measures for improvement.

David Bartosch: In hearing Mr Honneth speak about his theory of justice, we must not forget that some developing countries still have a poverty problem. By the end of the day, there has to be a certain level of social wealth before one can establish a recognition-based system of social self-organisation to achieve the kind of fair distribution that Mr Honneth describes here. Regarding the latter, I feel compelled to mention Wang Yangming for the third time. He has proposed a procedure of practical exercise of moral conscience which, as a practice, might help to foster recognition of self and other. In every human encounter, we must consciously practise to respect and to recognise the other. From respect and recognition among family members, to the intersubjective exertion of moral freedom, to social freedom as the general foundation of a worldwide community of common destiny, we should constantly practise the insight that all human beings and all living beings form one organic whole on the surface of our planetary house, and that it is the recognition of the value and dignity of life which provides us with a way to lay the foundations for a truly humane and prosperous future.

点击右上角![]() 微信好友

微信好友

朋友圈

朋友圈

请使用浏览器分享功能进行分享